IN WHICH WE DO OUR ‘ONE MAD THING A YEAR’ ALONG THE SLIEVE BLOOM WAY, GET A LITTLE WAYLAID AMONGST THE PINES, AND INVENT A NEW TERM FOR UNPLANNED DETOURS…

From a toponymic point of view, Slieve Bloom takes its name from an ancient mythical character called Bladma. As it’s old Irish, the ‘d’ is silent. Indeed, even in modern Irish, if you need to bluff your way in a pub quiz or something similar, it’s a safe bet when you see a ‘d’ in the middle of an Irish name that it probably won’t be heard in the pronunciation. For example, Tadhg sounds like ‘tige’. Sadhbh sounds like ‘sive’.

Slieve is just an anglicisation of the Irish sliabh, which means mountain. It’s pronounced ‘shleeve’.

Of course, these old mythical tales are impossible to decipher or validate. But the one aspect I quite like, from a runner’s perspective, is that the Modern Irish meaning of bladhm is ‘flame; flare up.’ And if you are trying to walk around this mountain range in a day, various parts of you, such as your groins, might indeed flare up.

Although the highest point is a modest 527 metres, because the Slieve Blooms stand alone in the midlands of Ireland, straddling Offaly and Laois, they naturally stand out. And they are amongst the oldest ranges in Europe, and would have once boasted some of the highest peaks. Erosion has seen to that. I know how they feel…

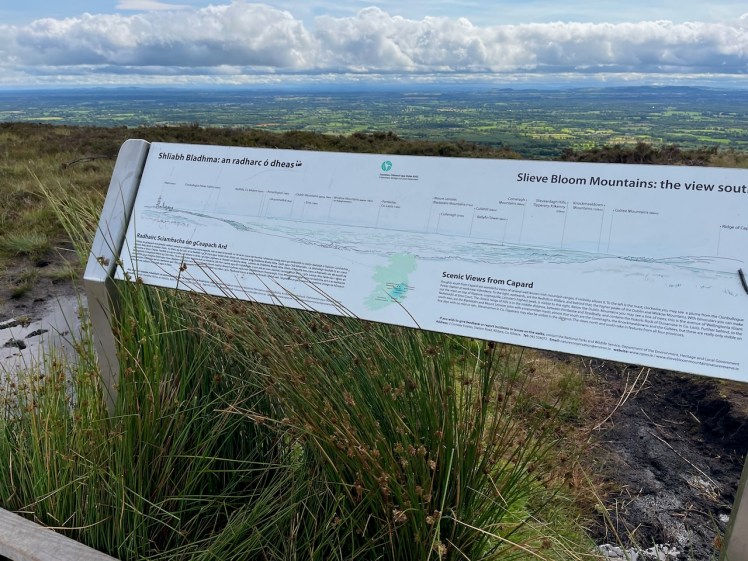

Due to their central location in the ‘hidden heartlands’ of Ireland (the latest tourist board ‘unique selling point’), you can see much of the country, on a clear day, if you get the right viewing point. Certainly, peaks from all of the provinces.

Like many uplands in Ireland, ownership is shared between Coillte (the national forestry body), NPWS (the National Parks and Wildlife Service) and private owners who farm the surrounding fringe uplands. Here is some blurb from the NPWS website:

The Slieve Bloom Mountains Nature Reserve is, at over 2,300 hectares, Ireland’s largest state-owned Nature Reserve. It was established in 1985, so that it could be managed in such a way as to ensure the conservation of the mountain blanket bog ecosystem. In addition, the Nature Reserve is designated a Ramsar Wetland Site and a Council of Europe Biogenetic Reserve. Much of the greater upland area has been designated as a Special Area of Conservation (SAC). The primary interest of the SAC is mountain blanket bog. The Slieve Bloom Mountains are also designated a Special Protection Area (SPA), of special conservation interest for the hen harrier, a rare bird of prey.

Indeed, the mountain range is so old and eroded that there are few peaks, per se, and much of the upland is a plateau dominated by heather and blanket bog. From here spring numerous valleys, often carved deep into the rock after thousands of years of erosion from the streams that pour out of the boggy upland. Everyone knows that Ireland’s longest river is the Shannon, but not so many could tell you the second-longest: it’s the Barrow, and it rises in Slieve Bloom. The flanks are dominated by Sitka Spruce plantations, courtesy of Coillte, and then below that, the trees give way to farmland. If you choose to take on the Slieve Bloom Way, you will pass through all of these various landscapes.

Pedants can point out that anything below about 600 metres is normally called a hill. And as nothing here rises to that height, my title – a hike in the hills – is apt. Plus it’s alliterative, so it’s ticking unironedman boxes galore.

Preamble over. Let’s get to the main amble, shall we?

My ‘one crazy thing per year’ adventure was supposed to be the Western Way, or at least, a section of it in Mayo. The fall off the roof not only banjaxed me physically, it seemed to knock the motivational stuffing out of me too. I found it hard to commit to the gym, and runs became sparse; more than one a week, but less than two (about 44kms in May, 73kms in June). I consoled myself that walking the dogs was still exercise. One small highlight was when my old fire service and running colleague, Ciaran, dragged me along for a 5 mile road race, and we managed to get in under 40 minutes.

It is a rare thing indeed that I come to a sensible decision (when a more stupid one is readily available), but I knew in my heart that the Western Way was beyond me this year, so I began the search for a more modest proposal. The Slieve Bloom Way was the ideal fit. It’s just over 70kms in length. It’s a looped route, and it’s only about 90 minutes drive from home. Gary was on board straight away, and the logistics were simple enough: two cars down early in the morning, park one about halfway, then on to the chosen start point, and get going. It didn’t really matter where we started as we would finish at the same point, but Kinnitty village trailhead seemed about right, and about 45 kms along the route, going anti-clockwise, was Clonaslee, for our car drop.

Once we had chosen the day (Friday 19th July), it was just a question of packing up the various potions and lotions and spare bits and bobs that make these sorts of adventures slightly less painful. The alarm was set for 3.30am and the traditional porridge and banana breakfast was washed down with tea. As I pulled into the cul-de-sac where Gary lives in Maynooth, he was already out with his phone, documenting the day.

The trip down was uneventful, and we stopped at Clonaslee first; the trick here was to make sure the various bags were in the right places: our own backpacks/hydration vests needed to come with us to the start, along with any clothes and food you might fancy when you finish, with the bulk of the refreshments at the stop-off point. That done, it was off to Kinnitty, park up, and get going.

The first section was uphill, so there was plenty of walking. A short section of downhill allowed us to do some light running. We were in Glenregan. There were some fine views over the valley as we cleared the trees. We were both wearing light running T shirts, but the weather was breezy and a heavy mist obscured much of the higher ground. We both had light rain jackets with us, but for now, we were hoping that we wouldn’t need them.

The trail ended, and we found ourselves on our first stretch of road. We were very exposed here, but resolved to plough on, and avoid admitting defeat and reaching for the jackets. As the road rose up before us, the mist grew thicker. Somewhere along this section, we crossed over from Offaly into Laois. There was a distinct ‘An American Werewolf in London’ vibe about this location (Gary preferred a zombie apocalypse reference). We hit the highest part of the route around 8.5 kms in, at 454 metres, and nearly missed a sneaky left that plunged down through a small gap into another heavily-wooded valley.

We reached an abandoned building and yard that doubled as a car park. There was an information board and a composting toilet, which was handy. We made it our first official pitstop. We headed out into another pleasant valley only to come across our first of several conundrums. Along a neatly fenced road there was a gate into a private house. Opposite this closed and padlocked gate was a yellow man sign, pointing in that direction. We jogged on down the road, confident that it must be a mistake, and that we would find another marker plaque to confirm we were on the right path.

Reader, we did not.

At this point, I need to explain this was the genesis of the phrase ‘doing a D’Arcy’. The D’Arcy in question is not Mr. D’Arcy of Pride and Prejudice fame. Rather it refers to D’Arcy’s Bridge on the Royal Canal in Killucan, Co. Westmeath. It was the bridge I missed crossing when I took on the canal as a triathlon during Covid. It became something of a running joke (ho, ho!) and it was officially coined on Slieve Bloom. We had actually already made a slight navigational error prior to this, not long after we had set off, but the second mistake was far bigger, and added about four kilometres on to the total.

As we returned somewhat bemused to the gate we had passed, the phrase popped into my head: doing a D’Arcy. From now on, any time we went wrong, we would have done a D’Arcy on it. We had no choice but to climb over the ornate wooden gate and proceed cautiously up the manicured driveway. Halfway up, on the right, was a small gap in the beech hedging, with a gate. This was also locked and laced with barbed wire. But there was a yellow man plaque pointing off into the field. All very random, but the GPX map suggested this was indeed the right course of action, so we clambered over. Gary cut himself on this gate, which was annoying. We traipsed across the field and found another marker and a stile. We were back in action.

The route was very pleasant here, as I recall, and we emerged from the forest into Monicknew car park. We decided to push on up the hill. There were more lovely wooded paths to clamber through before we emerged onto fire roads. I haven’t travelled all of Ireland’s uplands (that would be a nice project!) but I suspect few have been spared the scourge of Sitka Spruce. This is the main crop planted by Coillte, the forestry semi-state. And when I say fire roads, what I really mean are forestry access roads.

during construction are still visible

(Let us take a small diversion here, to talk briefly about this issue. Here is some blurb: ‘The land area of Ireland is 6.9 million hectares, of which 4.3 million hectares is used for agriculture or about 62% of total land area, and 724,000 hectares for forestry or about 10.6% of total land area.’ And of that land, Coillte manages about 440,000 hectares, and about 300,000 hectares are Sitka Spruce. Why is this an issue? If you are in the forestry business, it is not an issue at all, of course. It’s just business. Coillte have been diversifying of late into tourism. It’s a good step, on the whole, and it’s been brought about by pressure from various groups. But their mainstay is still Sitka.

Ecologically, blocks of spruce, planted and clear-felled on rotation, are devastating for wildlife and habitats. The trees are not native and do precious little to support local species. Because Sitka can grow on poor soils and is shade-tolerant, the uplands – which are deemed unproductive from a farming viewpoint – are the obvious location. Planted close together in symmetric rows for easier harvesting, a block of maturing spruce is a dark place! If you’ve ever stepped off a trail into one of these forests and explored under the trees branches, you will discover a gloomy, mossy environment, quite unlike a traditional mixed deciduous woodland with a higher canopy, and more light, and with a diverse undergrowth. In a Sitka forest, it is all rows and drainage channels, and decaying branches snagging your jacket. The scent is pleasing, of course, assuming you like that pine-fresh smell! The downside is when this is clear-felled, leaving behind an apocalyptic landscape that is all but impossible to traverse, even if you wished to.

Slieve Bloom differs from a lot of Irish mountain ranges in that it is not overgrazed by sheep. The misconception about the uplands in Ireland is that they are ‘no good’ for anything, and may as well be used for a variety of activities, including forestry, sheep grazing and wind-farms. Each of these has merit, as does sustainable tourism such as hillwalking and birdwatching. But the idea that these are barren areas to be exploited is incorrect; Irish mountains are not high, in the general scheme of things. Left to their own devices, native flora would eventually take hold, and we would have large swathes of oak and ash woodland with lots of other species mixed in, such as hazel, blackthorn, rowan, holly, birch and alder, plus a raft of native shrubs and plants. The other vital habitats are the blanket bogs. These differ from the lowland raised bogs which were once commonplace in the midlands (and provided turf as fuel for generations). They are not as deep, hence the name ‘blanket’, but they are an important home for many plants and animals unique to wetlands; they soak up and store vast amounts of water, and they are a carbon sink.

Over the years, many of these bogs have been, at best, neglected. In some cases, harvested to extinction, or drained, which amounts to the same thing. And many have succumbed to forestry, as it is deemed marginal land. So forestry is something of an elephant in the room. Coillte’s approach is to try and encourage people into parts of the forests that are deemed tourist-friendly, and avoid clear-felling at these locations. Left alone, some of these older conifers start to look quite noble, and there is more light. They are also planting screens of native trees to hide the plantations. We’re going in the right direction, albeit at slow pace.

And to finish my diversion (are you still with me?), I recall meeting a few Coillte folk in my travels. Once, whilst doing a graphic design job for the NPWS. I met a gent called Richard Jack who showed me around Capard. A mine of information. From what I can tell, he retired about two years ago. I hope he is still going strong. In a different life, I met a few of the old saw men when I was doing chainsaw courses with the fire service. These were hardy folk. They would spend weeks on end in all weathers out in the most remote woodlands with just their chainsaws, a few cans of petrol and some packed lunch. This was before the times of mechanical harvesters when all trees were felled by hand, snedded (stripping the small, side branches), cut to size and dragged to a central point and stacked for collection. Their quota was sisyphean. Different times.)

Let’s finish this ramble, shall we, and return to the original one.

Fire roads tend to follow contours. This makes sense for the heavy machinery that uses them. The surface is not pleasant to walk on; a mix of crushed stone, shale and gravel. They have design standards, naturally, and require 15 metres of clearance between plantations. They are usually cambered and culverted each side for drainage, and a walk in an Irish planted forest will be accompanied by numerous warnings not to climb on stacks of timber. These roads tend to be switchbacks, to minimise the gradient. From a walker’s perspective, this can be a little frustrating. It messes with your sense of direction, and adds extra distance to your journey.

And as we headed east towards Capard, we were thrown another spanner, unbeknownst at the time. A road left was closed. We continued on straight. The road started to dip down southwards, where we sensed we should be heading higher up to our left. After a quick check of the GPX again on the phone, we could see the little blue dot and the thin black line had parted ways, and the road we were on was not going to rejoin the route any time soon.

We had three choices; plough on, and hope to find a way back on to the trail. Retrace our steps to the closed road we were supposed to take (but clearly there was a reason it was closed), or take a third way, and go off-road. It was another D’Arcy moment. As we pondered our decision, I heard a Raven croak somewhere above us. I took that as sign and suggested we have a small adventure. We found an opening in the trees and used drainage channels to make our way uphill. The change in light was instant, as was the change underfoot. Thick moss hiding pools of mud, branches to snag and trip the unwary traveller. But it was cool and the breeze could not find us here, and we ploughed on, sure in the knowledge that eventually we would rejoin the path.

We were guided by a patch of light, and soon broke from the cover of the conifers to a boggy, heathery opening, and then a path of sleepers appeared. Up above, looking down on us, was the Stoney Man. The ravens croaked again. When birds call, they are usually defining their territory, looking for a mate, or perhaps warning of predators. In this instance, I am confident one raven was saying ‘look at these two fuckin’ eejits!’ to his mate as we rejoined the Way. Our spiritual moment had passed 😉

We stopped at the Stoney Man to admire the views. I suspect this is why it exists at this point, as it commands a fine panorama. That said, I don’t think it’s an ancient cairn. It may not even be a hundred years old. We left it behind, along with our little adventure, and continued on eastwards towards the Ridge of Capard. We were out in the open now, and there was no shelter from the breeze. On the plus side, the sun had come out and burned off the last of the mist, so the jackets remained in the backpacks. The track here is timber sleepers, and for the most part, this is ideal, as they sit on top of heather and open bog. But on occasion, and without any reason, these tracks just end and you have to pick your way through the muddy wetland, hopping from tussock to rock and back again, hoping not to come a cropper. And then another section of sleepers appear and you begin the hopscotch routine all over again.

Up ahead, I could see the Metal Man. I pointed this out to Gary, who always diligently does his research. He hadn’t realised that the ‘metal man’ is actually a large and heavily festooned telecoms mast. I couldn’t resist:

‘Do you know why it’s called the metal man, Gary?’

‘No… why?’

‘Because the locals burned down the first three wicker men…’

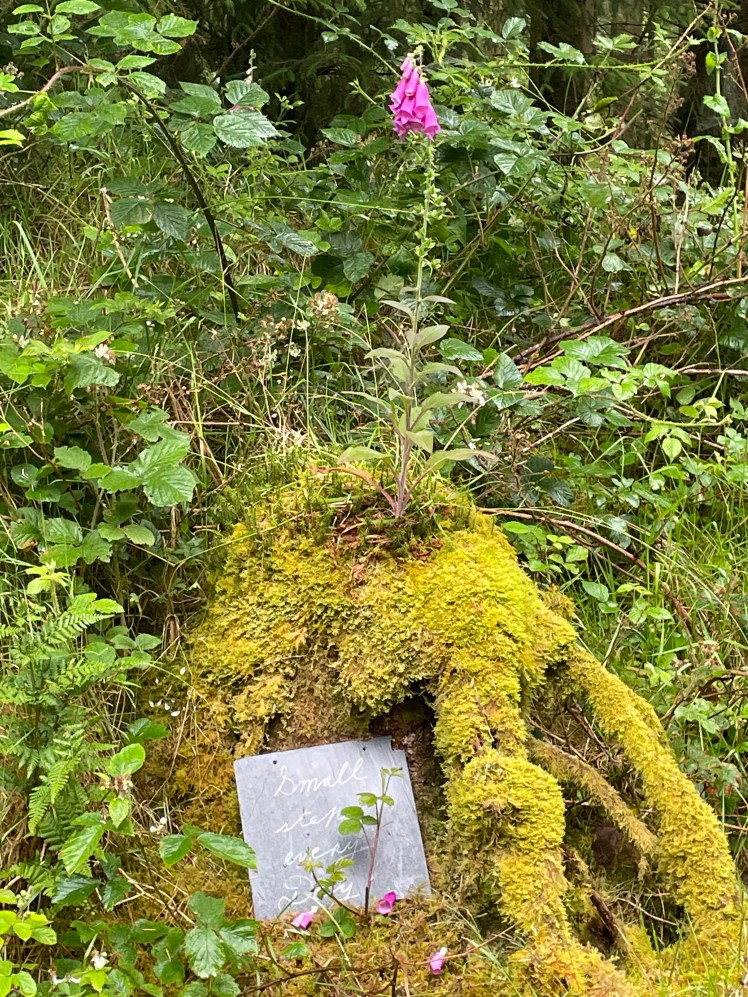

Shortly after this awful gag, we took a small and deliberate detour to the viewing platform. Here, I was pleased to see that my signs are still here and in good shape. It was a design project from many moons ago. So long, indeed, that I can’t even put a year on it. The idea was to give visitors an idea of what can be seen from this magnificent vantage point. To the south-west is Stoney Man from where we had come, and at a lower level to the north-east was the low ridge upon which sat the Metal Man. From here, on a clear day, you can see the Dublin and Wicklow Mountains, the Blackstairs in Wexford, the Comeraghs in Waterford, the Galtees in Tipperary, and not forgetting the Knockmealdowns. And now that I think about it, this covers all the most recent adventures: the Wicklow Way, obviously, plus Declan’s Way from the year before; the Barrow Way is also here, in various guises: the river rises here, and we would be meeting it shortly, in its exuberant youth, and where that trail ends in St. Mullins is overlooked by the Blackstairs Mountains and Mount Leinster. Perhaps the Right Royal Triathlon is the only one that has no visible point of reference, but the canal is out there, nestled in the midlands of Ireland.

To the north, sweeping left from Capard, the masts at Wolftrap Mountain peek above the ridgeline. Following Tinnahinch, you might pick out Slieve Bán in Co. Roscommon, or Slieve Anierin in Co. Leitrim, or perhaps the Cuilcagh Mountains which straddle the border, where the mighty Shannon begins its long journey to the sea. Or you might spot Loughcrew and its ancient megalithic passage tombs, or even Croghan Hill, which is actually an extinct volcano, and close to the site where an Iron Age bog body was unearthed.

We were on a slow descent towards Glenbarrow. The trail here is in more open ground with scrub vegetation before rejoining some old, mixed woodland. We joined the Barrow here and followed it downstream in what is a large loop which almost doubles-back on itself. Our reward was a delight; a new café beside the Glenbarrow car park, serving the most delicious sausage rolls, and as a bonus, hot chocolate with a mountain-size dollop of cream and Stoney Man-sized heap of mini marshmallows. We were not all that far from the car, but it was a unanimous decision to rest our weary bones here, and chat to fellow travellers. A large shaggy hound was offering his services for anyone unable to finish their lunch, which was a nice touch. His name was Toby.

We pressed on, feeling, if not totally refreshed, at least happy in our bellies. Glenbarrow is one of the jewels in the Slieve Bloom Way crown. The river gurgles and chatters away down below, and the star attraction is Clamp Hole Waterfall. It’s not particularly large or high, but you can get down amongst the rocks below the falls and really enjoy the sights and sounds first hand. I stripped off my shoes and socks and gave my feet a good soaking in the peaty waters, and even though I had to put damp socks back on again, it was a pure delight.

We left the river behind and found more pleasing woodland and climbed out of the valley towards Tinnahinch. The woodland here was a pleasure to stroll around, but we soon reached the top of the valley and were thrown back onto fire roads again. And then the fire road spat us out onto an open, tarred road, From here we descended slowly out of reach of the mountains altogether, and came to a farm which we had to pass through. The farmer’s two Jack Russells came out to greet us (well, if you know the breed, that’s not how they approached us initially, but a few ear rubs and all was well!). We were literally passing through open fields, amongst cattle and sheep, searching for the next marker post. Our feeling here was that this was definitely the road less travelled, compared to the popularity of Glenbarrow, Capard and Stoney Man. But on the plus side, at least this landowner hadn’t locked his gates or covered them in barbed wire…

And then we were back on open road again. Off to the left, Slieve Bloom looked like a recent memory. We trudged along, with the next port of call being the car at Clonaslee keeping our spirits up. The sun was still out, and I was alternating between getting some much-needed sunshine on my mush, but also popping the cap back on so I didn’t catch too much on my balding head. I had been sipping quite regularly from my hydration pack, and had sank a full bottle of cold peach tea along with my hot chocolate. But despite this, I couldn’t remember the last time I’d stopped for a wee. So I was getting dehydrated.

We found some shade and very pleasing deciduous woodland at Brittas, and this led us to the trailhead at Clonaslee, but not before another minor D’Arcy where we discovered we were on the wrong side of the river, and had to do an impromptu fording over some rocks.

Once at the car, shoes and socks were stripped off, phones were put on charge, and Gary revealed his master stroke; two cold bottles of (non-alcoholic) Erdinger beer. It is an ideal complement to a cheese sandwich, as it happens. Hydration packs and bottles were refilled, and we both changed shoes and socks. Gary’s choice for the first chunk of the Way had been a pair of Inov8s. These proved useful on the few technical sections, but there were very few of these, in truth. A pair of regular road running shoes would have probably worked fine, and there is no bounce at all with Inov8 runners, as Gary pointed out on a few occasions. I was wearing my Hoka Speedgoats, and they worked a treat. I changed into a pair of Saucony Peregrines. These are perhaps a more technical runner than the Speedgoats, but the main thing was that they were clean and I had fresh, dry socks to match. Delicate areas were re-lubed, and I donned a fresh T-shirt.

We had more open road to contend with before the route finally dipped back into the lower flanks of Slieve Bloom. It was a mix of fire roads and forestry plantation, but at least it felt like we were back on the Way. We stopped briefly at the Giant’s Grave. This is the megalithic tomb of the ancient warrior who gives the mountains their name. It was once a barrow grave, but the years have not been kind, and the five or six rocks half buried in the thick grass are perhaps not much visually if you have made the effort to get here.

Soon after, we passed unceremoniously from Laois back into Offaly again. The Way takes a loopy detour all the way out another trailhead at Cadamstown, but the reward is the Silver River Gorge. The river here is even more impressive than Glenbarrow, but I suspect gets fewer visitors. It’s well worth the effort, though I would seriously question the manner in which the wooden fencing has been installed to stop the unwary visitor from plunging to a sticky end. We were both flagging at this stage with about 65kms on the clock.

The pleasant surroundings of Kinnitty Castle were a balm, with some open fields and streams, ruined cottages and old growth woodland. The route wended its way through the trees, and we followed along. I was aware that with our inadvertent D’Arcys plus various stoppages, not to mention our glacial pace, that we might start to lose the light. We had both packed head torches at Clonaslee, just in case.

And then I nearly trod on a badger. It was snuffling around in the grass beside the trail and took off at a rate of knots to find sanctuary in the thicket, away from clumsy hikers.

This little oasis of loveliness would have been a fine place to end our journey, but Slieve Bloom and Coillte are always here to remind you that planted forestry, for now, holds sway, and we soon left the Kinnitty Castle hinterland behind and found fire roads once more. The light dropped even further and Gary fished out his head torch. He lead the way and I tagged in behind, following the beam. With our various detours, we knew we would not be stopping at 70.3kms – the official distance. But we weren’t sure at this stage how much extra was in store.

Those last few kilometres did seem to drag on, and I thought I caught a glimpse of the car park barrier once or twice in the gloomy shadows. Tricks of the light. To add to the excitement was the possibility of one final D’Arcy where we overshoot the runway (we were not 100% sure we were on the right path either) and plunge on past the trailhead and start the journey all over again. The worst kind of Groundhog Day!

But then the barrier did appear, and then my car, just as we had left it 16 hours ago. Gary fished out two more bottles of Erdinger and we celebrated in alcohol-free style. Some warm clothes, a few minutes to wind down, and then it was back to Clonaslee to pick up Gary’s car and head for home.

Some stats: 16 hours to get around, with nearly as much time idling (lunch stops, rest breaks, photos, etc.) as running (2.27 run time, 2.21 idle time) with the other 11 plus hours spent hiking. As Gary pointed out already in his own social media posts, neither of us are at peak fitness right now, but we both reckoned we needed a challenge.

Would I recommend the Slieve Bloom Way? If this sort of thing floats your boat, then yes, of course. If you want to pluck the low-hanging fruit, then investigate the various trailhead loops and avoid some of the less-attractive sections. The Way is not, as I had mistakenly thought, a circumnavigation of the range, but rather it cuts through the middle and loops around the top half. The signage is mostly fine, but there are obviously a few problems as we discovered, and they need to be rectified. Some sections are clearly more popular than others, and these are getting the attention in terms of signage, trail management and services. Glenbarrow, for instance, is the only point on the Way with a café. So whilst you can’t argue that Slieve Bloom Way is a totally wild and remote experience, you are going to be on your for large parts of the journey, and need to be self-sufficient.

Whilst I’m here, I should mention Larry Mahony, who holds the FKT on this route at just over 6 hours and 55 minutes. Just to show you how slow we were this weekend!

My GoPro let me down for the first time since I started using them. The card became unreadable after a few hours on the trail. We have clips from both our phones, so the bad news is that there should be enough footage to make a short film 😉

That said, software is available, should I wish to go that route, which suggests I can rescue the footage from the micro SD card. If I choose to shell out and buy it 😦

In other news, we witnessed one of the best All-Ireland Hurling Finals in living memory on Sunday, between Cork and Clare. It went to extra time, and Clare pipped it by a point. I gather the BBC showed it in full on their main UK channel and it seems to have really piqued the interest of my brothers and sisters across the pond. Well done, all. A great testament to an amateur game, and a fine advert for the country.

And finally, I suspect some of you are still on Facebook. I am, as it happens, though I don’t use it very often. But what I do get regularly are messages from the company to let me know of a ‘memory’, should I choose to view it and make it public again. I don’t know all the algorithms involved in choosing these memories, and I don’t wish to. It seems like a pretty naked attempt to generate more traffic to a site that has been slipping down the rankings, year on year.

It brought to mind a Wim Wenders film I watched many years ago, called Until the End of the World. Without going into detail, there is a device that allows the wearer to access old memories and relive them over and over again. Tennyson’s Lotos-eaters also comes to mind (though it was a dirge of a poem to inflict on young readers; perhaps it would have been more exciting if they had got us all stoned first…)

One can easily see how such a device could keep the user in a soporific state, like a habitual drug-user. In the end, you would simply waste away, watching old memories on repeat.

And I’m not really sure why I am bringing this into the blog, really, other than to say ‘fuck Facebook’ and all that social media bollocks. Stop rehashing old memories and start making some new ones 🙂

As always, fabulous to team up with Gary for this latest adventure, so huge thanks for all the prep work prior to getting on the road, and for keeping the show on the road as we progressed around. Several of the photos above are Gary’s. I will have a stab at yet another short film when the time allows, and this too will feature plenty of footage from Gary’s perspective.

And so, bring on the Olympics!

What a great adventure! Having learnt from my baby ultra that walking is a legitimate of crossing the terrain, it’s opened up longer options for me too (not quite as long as yours!). I just to find myself a Gary!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Definitely having a partner in crime makes these capers possible. Your Gary is out there somewhere, I just know it 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s terrific. If you’ve not copyrighted it, I would like to use ‘doing a D’Arcy’ in the future. I am also rather taken with ‘I nearly trod on a badger’ but am not sure how it should be used in general, save as some sort of euphemism ….

LikeLiked by 1 person

Cheers. ‘Doing a D’Arcy’ is yours to cut out and keep. Though without context, I suspect most folk will assume you are pretending to be Colin Firth. So use with discretion. As Colin would.

As regards treading on badgers… I fear if my mind goes down that dark alley, it may never come back. If you find a good use for it, let me know. Bonus points for combining the two!

LikeLiked by 1 person

A very understated and typically eloquent description of what was a great achievement. Even more so considering what you went through earlier this year. Well done 👏 👏 👏 👏 👏

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Niall, much appreciated. I know it’s a bit out of your territory, and I haven’t exactly sold it (!), but have you been to the Slieve Blooms? It does have some lovely walks, and is worth the trip.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have been there. It was back in January 22 for a geocaching social event. Based around Glenbarrow and also walked part of the Slieve Bloom Way. I knew the signs you described before you showed the photos. Great job 👌

It was a damp day (after lots of wet days) so the river and waterfalls were impressive…

LikeLiked by 1 person

LikeLike

The infamous D’Arcy Bridge

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh, the horror!

LikeLike

What massive achievements – the adventure and the post, both! From my distant vantage, the fire roads and such didn’t bother me in the least. I am greatly bothered by locked gates and barbed wire blocking hikers’ right-of-way, though. Seems positively un-Irish!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Cheers my dears. Alas, I would say that a positive dislike of rambling is a very Irish thing indeed. The right to roam is not enshrined in our DNA like in some other countries. Even the UK have a better attitude to hiking and camping. It may be an Irish throwback to the days when we were thrown off our own land, perhaps. Hence the existence of plays like ‘The Field’, which really expose the mania that a piece of land can stir up.

LikeLike